When I first arrived in Jatiwangi I didn’t imagine I would find myself working in a roof-tile factory. In Jatiwangi I took part in the

Jatiwangi International Performance Artist in Residence (JIPAR) 2006. Participants included artists from all over the world, including

Greece,

Germany,

Australia,

Finland and

America. I arrived in Jatiwangi early, for a stay of six days, where I resided in the home of the Jatiwangi Art family, a family of four brothers, their lovely wives, children, mothers, aunts and uncles. From there I was taken on tours of the area of Jatiwangi and Jatisura, which is located in the Majalenka area of

West Java, an area of spanning rice fields, far-off mountain ranges, and what I would soon come to know well, hundreds of roof-tile factories.

My first introduction to the roof-tile factory was within the Jatiwangi Art Factory itself. Run by some of the family members, the roof-tiles made traditionally by hand by a local staff of about 25 employees. From early in the morning until late at night, hundreds of roof-tiles are in the process of being made, formed from big chunks of clay, laid out to dry and at night stacked into a large brick kiln and burnt to form a nice, solid red clay roof-tile. At night you can hear the crackling of the fire, watching its hot orange flames stretch out to the sky.

My first introduction to the roof-tile factory was within the Jatiwangi Art Factory itself. Run by some of the family members, the roof-tiles made traditionally by hand by a local staff of about 25 employees. From early in the morning until late at night, hundreds of roof-tiles are in the process of being made, formed from big chunks of clay, laid out to dry and at night stacked into a large brick kiln and burnt to form a nice, solid red clay roof-tile. At night you can hear the crackling of the fire, watching its hot orange flames stretch out to the sky.

Another tour took me to see the modern roof-tile factory. A large compound of sprawling buildings and security gates, large amounts of roof-tiles are produced and packaged every day. Inside the factory was a cacophony of dust, the constant sound of machines and large equipment being moved around continuously. Unlike the traditional factory which sells its roof-tiles locally in Indonesia to neighboring islands like Sumatra and Sulawesi, the modern factory, owned by a French company, exports as far as Italy, France, and America. Although the target daily production in the traditional factory is much less than the modern factory, the amount of staff in the modern factory almost seems less than in the traditional! With the machines doing all the work, less people are needed to do the job.

Another tour took me to see the modern roof-tile factory. A large compound of sprawling buildings and security gates, large amounts of roof-tiles are produced and packaged every day. Inside the factory was a cacophony of dust, the constant sound of machines and large equipment being moved around continuously. Unlike the traditional factory which sells its roof-tiles locally in Indonesia to neighboring islands like Sumatra and Sulawesi, the modern factory, owned by a French company, exports as far as Italy, France, and America. Although the target daily production in the traditional factory is much less than the modern factory, the amount of staff in the modern factory almost seems less than in the traditional! With the machines doing all the work, less people are needed to do the job.

With a desire to know more about the experience of working in both of these factories, I arranged through the Jatiwangi Art Factory to work two full work days, one in the traditional factory, and one in the modern.

On my first day of work at the traditional factory, I awoke at 5:30am. Arriving to work at 6am on a borrowed bicycle, I was greeted by large smiles of curiosity from the other workers. I was put to work with the women, stacking newly pressed roof-tiles up on large drying racks made from bamboo, and moving the ones from the day before out into the sun from which they would later be taken to burn in the kiln. The smell inside the factory was of earth and clay. Several of the workers had brought their small children to wait while they worked, who played on handmade swings amongst the piles of clay. The sun shone through the wide open doors and dangdut, Indonesian popular music, played on the small radio. Within those eight hours, I was amazed at the agility of these people, their physical strength and ability to work so hard every day at something that is incredibly demanding physically, for a mere pay of 10,000 rupiah (a little more than $1) for one full day’s work. After only two hours, my arms were already tired, my back ached, I was hot and sweaty, but the momentum of everyone working together kept me going until the end. After work I was invited to visit each worker’s home, seeing the simplicity of the way they lived, meeting their children and families, and trying to imagine how their lives might be working hard every day just to manage to put food on the table for their families. What moved me was their generosity, openness, and the constant smiles on their tired faces.

On my first day of work at the traditional factory, I awoke at 5:30am. Arriving to work at 6am on a borrowed bicycle, I was greeted by large smiles of curiosity from the other workers. I was put to work with the women, stacking newly pressed roof-tiles up on large drying racks made from bamboo, and moving the ones from the day before out into the sun from which they would later be taken to burn in the kiln. The smell inside the factory was of earth and clay. Several of the workers had brought their small children to wait while they worked, who played on handmade swings amongst the piles of clay. The sun shone through the wide open doors and dangdut, Indonesian popular music, played on the small radio. Within those eight hours, I was amazed at the agility of these people, their physical strength and ability to work so hard every day at something that is incredibly demanding physically, for a mere pay of 10,000 rupiah (a little more than $1) for one full day’s work. After only two hours, my arms were already tired, my back ached, I was hot and sweaty, but the momentum of everyone working together kept me going until the end. After work I was invited to visit each worker’s home, seeing the simplicity of the way they lived, meeting their children and families, and trying to imagine how their lives might be working hard every day just to manage to put food on the table for their families. What moved me was their generosity, openness, and the constant smiles on their tired faces.

T he next day my body felt quite sore, my arms especially. But this didn’t stop me from getting up early once again, and heading to the modern factory to keep my promise of working there for a full day in comparison. Entering the modern factory is much different than entering the traditional. The chaos of sounds and movement of large machines has the ability to instantly throw you off. I was set up to work with a small group of people, both men and women, at the roof-tile forming machine, where clay was put in and formed roof-tiles came out in a long moving line. Each worker had his or her own specific task off cutting off the rough edges, repositioning the tiles, and at the end setting them one after the other on large trays. Once a tray was full it was moved to a drying room and immediately replaced with an empty tray. While it was the same kind of repetitive process as in the traditional factory, I found this work to be draining much more quickly. Not after twenty minutes of work I was already feeling quite lightheaded, difficult to concentrate, my eyes straining to focus on the fast-moving tiles going past me. How, I wondered, could these workers manage to do this every day? I think I would go crazy! But the more I talked with them, the more I understood that working in this factory was not a matter of choice, but a matter of survival. Every day these workers work from seven in the morning, until seven at night, often working overtime due to a high output rate for each day and a slow-working machine, getting paid a mere 25,000 rupiah (about $3) per day. Many of them took special medicine to reduce headaches caused by the fast-moving trays and loud sounds. They managed to survive the hard work by building friendships amongst themselves, making jokes and chatting as they worked. After six hours of work in the modern factory, I went home exhausted, going straight to sleep and trying to shake off the repeated sounds of machines in my head.

he next day my body felt quite sore, my arms especially. But this didn’t stop me from getting up early once again, and heading to the modern factory to keep my promise of working there for a full day in comparison. Entering the modern factory is much different than entering the traditional. The chaos of sounds and movement of large machines has the ability to instantly throw you off. I was set up to work with a small group of people, both men and women, at the roof-tile forming machine, where clay was put in and formed roof-tiles came out in a long moving line. Each worker had his or her own specific task off cutting off the rough edges, repositioning the tiles, and at the end setting them one after the other on large trays. Once a tray was full it was moved to a drying room and immediately replaced with an empty tray. While it was the same kind of repetitive process as in the traditional factory, I found this work to be draining much more quickly. Not after twenty minutes of work I was already feeling quite lightheaded, difficult to concentrate, my eyes straining to focus on the fast-moving tiles going past me. How, I wondered, could these workers manage to do this every day? I think I would go crazy! But the more I talked with them, the more I understood that working in this factory was not a matter of choice, but a matter of survival. Every day these workers work from seven in the morning, until seven at night, often working overtime due to a high output rate for each day and a slow-working machine, getting paid a mere 25,000 rupiah (about $3) per day. Many of them took special medicine to reduce headaches caused by the fast-moving trays and loud sounds. They managed to survive the hard work by building friendships amongst themselves, making jokes and chatting as they worked. After six hours of work in the modern factory, I went home exhausted, going straight to sleep and trying to shake off the repeated sounds of machines in my head.

In a late-night conversation with some of the workers from the traditional factory, who worked to tend the fire of the kiln, I learned more about the pros and cons of both modern and traditional factories. One con of the traditional factory is the waste of wood used to burn in the kiln. The worker stated that they’re killing the forest to make roof-tiles, but can’t afford to put in a gas burner like those in the modern factory. He also pointed out that the roof-tiles that come out of the modern factory are much stronger, and will last longer than those of the traditional factory. However, life working in the traditional factory seems to be much healthier, with set breaks for eating together and resting every few hours, and no dependence on the non-stop moving machines as in the modern factory. Fresh air and sun came into the room, and the pace of the workers together was in sync and like one big family. Both factories did maintain a strong connection between all the workers, and a continual sense of togetherness and commitment to work based on survival. The traditional factory workers wage was lower, based on the fact that prices for materials to make roof-tiles have recently gone up, and it was all that the factory owners could afford to pay their employees. Higher pay depends on action from the government to take charge of laborers rights and honor the work that they do as essential to the economy.

In a late-night conversation with some of the workers from the traditional factory, who worked to tend the fire of the kiln, I learned more about the pros and cons of both modern and traditional factories. One con of the traditional factory is the waste of wood used to burn in the kiln. The worker stated that they’re killing the forest to make roof-tiles, but can’t afford to put in a gas burner like those in the modern factory. He also pointed out that the roof-tiles that come out of the modern factory are much stronger, and will last longer than those of the traditional factory. However, life working in the traditional factory seems to be much healthier, with set breaks for eating together and resting every few hours, and no dependence on the non-stop moving machines as in the modern factory. Fresh air and sun came into the room, and the pace of the workers together was in sync and like one big family. Both factories did maintain a strong connection between all the workers, and a continual sense of togetherness and commitment to work based on survival. The traditional factory workers wage was lower, based on the fact that prices for materials to make roof-tiles have recently gone up, and it was all that the factory owners could afford to pay their employees. Higher pay depends on action from the government to take charge of laborers rights and honor the work that they do as essential to the economy.

Through my two days of work, I managed to get an idea of what life might be like for the people who work in these factories every day. However, my experience is still far from complete. I would have to work there for a year, living on the wages that the other workers are living on, going to work every day six days a week to really know what the experience of working in a factory is like. As an artist, I had the advantage of working in the factory as an experiment, not as a will to survive. However, what I have learned is still something that not many people have the opportunity or even the desire to experience, and for that I am thankful. The largest influence for me was the friends that I made and worked with in the factory, their kindness and understanding, their welcoming of me into their work environment, open sharing and continuous laughs and jokes that made my experience, despite the hard work, a pleasant one.

Through my two days of work, I managed to get an idea of what life might be like for the people who work in these factories every day. However, my experience is still far from complete. I would have to work there for a year, living on the wages that the other workers are living on, going to work every day six days a week to really know what the experience of working in a factory is like. As an artist, I had the advantage of working in the factory as an experiment, not as a will to survive. However, what I have learned is still something that not many people have the opportunity or even the desire to experience, and for that I am thankful. The largest influence for me was the friends that I made and worked with in the factory, their kindness and understanding, their welcoming of me into their work environment, open sharing and continuous laughs and jokes that made my experience, despite the hard work, a pleasant one.

Country Fair I was sixteen years old, and to me then it seemed like a utopia of rainbows and wacky performances, costumes and wafts of marijuana. At 26, after spending two years in Indonesia and prior time abroad as well, I find myself more skeptical of that 'hippie' stuff, in many ways I don't feel myself as connected to it as I might have in the past. In spite of that, I took the opportunity offered by my good friends Gary and Liza from Seattle to take part in their 'Mighty Tiny Puppet Stage' and create a performance to perform two times a day at the fair, in collaboration with my boyfriend Lilik, who is newly arrived in America for his first time from Indonesia.

Country Fair I was sixteen years old, and to me then it seemed like a utopia of rainbows and wacky performances, costumes and wafts of marijuana. At 26, after spending two years in Indonesia and prior time abroad as well, I find myself more skeptical of that 'hippie' stuff, in many ways I don't feel myself as connected to it as I might have in the past. In spite of that, I took the opportunity offered by my good friends Gary and Liza from Seattle to take part in their 'Mighty Tiny Puppet Stage' and create a performance to perform two times a day at the fair, in collaboration with my boyfriend Lilik, who is newly arrived in America for his first time from Indonesia.  Oh overwhelming!! In the end the preparation for the performance was a bit more than I had expected, given the fact that we'd only been in America for a short time, still juggling everything between cultural adjustment, family, friends and being back. That in addition to my continuous search for what kind of performance I do want to create. My performance over the years has been such a mish mash of so many different things, sometimes I don't even know how to pin it down anymore!!

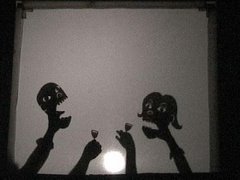

Oh overwhelming!! In the end the preparation for the performance was a bit more than I had expected, given the fact that we'd only been in America for a short time, still juggling everything between cultural adjustment, family, friends and being back. That in addition to my continuous search for what kind of performance I do want to create. My performance over the years has been such a mish mash of so many different things, sometimes I don't even know how to pin it down anymore!! I've strayed away from for a while in hopes of not getting locked into anything too specific, we decided to blend the world of Mr. Matterly, the famous green-headed know-it-all puppet from a previous show I did, 'The Secret Life of Isabel Jukes', with the world of the West Javanese mask dance I've been studying recently in Indonesia, 'Tari Topeng Cirebon'. This way, the audience would still have the visual eye candy of puppetry and masks, in addition to seeing something new and different, that of the dance, and perhaps even learn something about that place so far away that not many people, especially in America because it's so darn far, have even heard of!

I've strayed away from for a while in hopes of not getting locked into anything too specific, we decided to blend the world of Mr. Matterly, the famous green-headed know-it-all puppet from a previous show I did, 'The Secret Life of Isabel Jukes', with the world of the West Javanese mask dance I've been studying recently in Indonesia, 'Tari Topeng Cirebon'. This way, the audience would still have the visual eye candy of puppetry and masks, in addition to seeing something new and different, that of the dance, and perhaps even learn something about that place so far away that not many people, especially in America because it's so darn far, have even heard of!

two: "Do you do this dance professionally?" (well, um, not yet, still learning, which is why I'm returning to Indonesia in November!) Among other things....

two: "Do you do this dance professionally?" (well, um, not yet, still learning, which is why I'm returning to Indonesia in November!) Among other things.... publically, or dance in general, although it's something I've always loved to learn and do. That, in combination with puppetry and exploring new ways to meld some of the many things I do love doing together into one, which is a challenging task, but definitely one that I want to continue to conquer. That, in combination with some of the amazing performances I saw at the fair (The Yard Dogs, Jason Webley, Gamelan X, a hilariously funny guy who called himself 'Donny Wu' with a New York accent and tried to preach his yoga philosophy to the audience, with products for sale and all...!), resulted to be a truly inspiring experience, both from my own

publically, or dance in general, although it's something I've always loved to learn and do. That, in combination with puppetry and exploring new ways to meld some of the many things I do love doing together into one, which is a challenging task, but definitely one that I want to continue to conquer. That, in combination with some of the amazing performances I saw at the fair (The Yard Dogs, Jason Webley, Gamelan X, a hilariously funny guy who called himself 'Donny Wu' with a New York accent and tried to preach his yoga philosophy to the audience, with products for sale and all...!), resulted to be a truly inspiring experience, both from my own  efforts to explore what I do, and from seeing those of others and how they succeed.

efforts to explore what I do, and from seeing those of others and how they succeed.