Through time and exploration of different styles of dance and performance in Indonesia, I finally found my calling and passion of interest, 'Tari Topeng Cirebon', which means 'Mask Dance from Cirebon'. Cirebon, whose name is derived from the Sundanese words of "Cai" (or water) and "Rebon" (or "shrimp"), is a city on the north coast of the island of Java, approximately 297 km east of Jakarta, whose main production, hence the name, is fishing.

Through time and exploration of different styles of dance and performance in Indonesia, I finally found my calling and passion of interest, 'Tari Topeng Cirebon', which means 'Mask Dance from Cirebon'. Cirebon, whose name is derived from the Sundanese words of "Cai" (or water) and "Rebon" (or "shrimp"), is a city on the north coast of the island of Java, approximately 297 km east of Jakarta, whose main production, hence the name, is fishing.Tari Topeng Cirebon has been known to society since the 16th century, and possibly before that, although there is no written proof. The first person who made this dance become known throughout Indonesia was Sunan Kalijaga, one of the nine prophets, or Muslim ‘evangelists’ who brought the teachings of Islam to Indonesia. Sunan Kalijaga, who was the only prophet originally from Indonesia, was unique and perhaps the most effective, as he preferred to use alternative

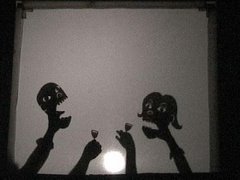

propaganda in spreading his teachings, using traditional Javanese art such as shadow puppetry, mask dance and music to reach the people, drawing from the stories of the Ramayana and Mahabarata. Around the 19th century, such dancers as Mimi Rasinah and Sudjana Ardja continued the preservation of this ancient mask dance, passed down through generations, making it further known through their gracefulness and devotion to this nearly lost dance performance form.

propaganda in spreading his teachings, using traditional Javanese art such as shadow puppetry, mask dance and music to reach the people, drawing from the stories of the Ramayana and Mahabarata. Around the 19th century, such dancers as Mimi Rasinah and Sudjana Ardja continued the preservation of this ancient mask dance, passed down through generations, making it further known through their gracefulness and devotion to this nearly lost dance performance form.Tari Topeng Cirebon tells the life journey of a person in society through five different mask characters, Panji, Samba, Rumyang, Tumenggung and Klana. Accompanied by a gamelan orchestra, each mask symbolizes a different phase in one’s journey from birth to adulthood, expressed through specific characteristic movements of the dancer, a variation of rhythms, and often active participation of the audience. Considered a sacred ritual

dance performance, Tari Topeng Cirebon can be experienced in an array of village ceremonies, including those highlighting worship of the ancestors, marriage ceremonies, harvest season activities, circumcisions, and important family and community gatherings. Vestiges or simplified variations of Tari Topeng Cirebon can also be seen today in new forms of dance, street busking performances, and certain small theaters in cities throughout Indonesia and the world. Still preserved principally by passing the lineage down from generation to generation, Tari Topeng Cirebon’s future existence will depend on the continuing interest of younger generations who are motivated to venerate their elders and traditional culture, a group that appears to be dwindling with time.

dance performance, Tari Topeng Cirebon can be experienced in an array of village ceremonies, including those highlighting worship of the ancestors, marriage ceremonies, harvest season activities, circumcisions, and important family and community gatherings. Vestiges or simplified variations of Tari Topeng Cirebon can also be seen today in new forms of dance, street busking performances, and certain small theaters in cities throughout Indonesia and the world. Still preserved principally by passing the lineage down from generation to generation, Tari Topeng Cirebon’s future existence will depend on the continuing interest of younger generations who are motivated to venerate their elders and traditional culture, a group that appears to be dwindling with time.